Lab 7: Randomized Complete Block Design

FANR 6750: Experimental Methods in Forestry and Natural Resources Research

Fall 2022

lab07_blocking.RmdRecap

Remember from lecture that randomized complete block design (RCBD) is like one-way ANOVA except experimental units are organized into blocks to account for extraneous source of variation.

Blocks can be regions, time periods, individual subjects, etc. but blocking must occur during the design phase of the study.

We can write the additive RCBD model as:

\[\large y_{ij} = \mu + \alpha_i + \beta_j + \epsilon_{ij}\]

Blocked ANOVA by hand

To “fit” the RCBD model by hand, we’ll use the gypsy moth data we saw in lecture:

| Treatment | Region | caterpillar |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 1 | 25 |

| Control | 2 | 10 |

| Control | 3 | 15 |

| Control | 4 | 32 |

| Bt | 1 | 16 |

| Bt | 2 | 3 |

Factors

So far, we have generally treated data as either numeric/integer if

the vector consisted of numbers, or character if the data consisted of

non-numeric information. To perform the RCBD analysis, we need to learn

about another type of object in R - factors.

Factors look like character strings but they behave quite

differently, and understanding the way that R handles

factors is key to working this type of data. The key difference between

factors and character strings is that factors are used to represent

categorical data with a fixed number of possible values, called

levels1.

Factors can be created using the factor() function:

Because we didn’t explicitly tell R the levels of this

factor, it will assume the levels are adult and

juvenile. Furthermore, by default R assigns levels

in alphabetical order, so adult will be the first level and

juvenile will be the second level:

levels(age)

#> [1] "adult" "juvenile"Sometimes alphabetical order might not make sense:

What order will R assign to the treatment levels?

If you want to order the factor in a different way, you can use the

optional levels argument:

treatment <- factor(c("low", "medium", "high"), levels = c("low", "medium", "high"))

levels(treatment)

#> [1] "low" "medium" "high"Sometimes you may also need to remove factor levels. For example, let’s see what happens if we have a type in one of the factors:

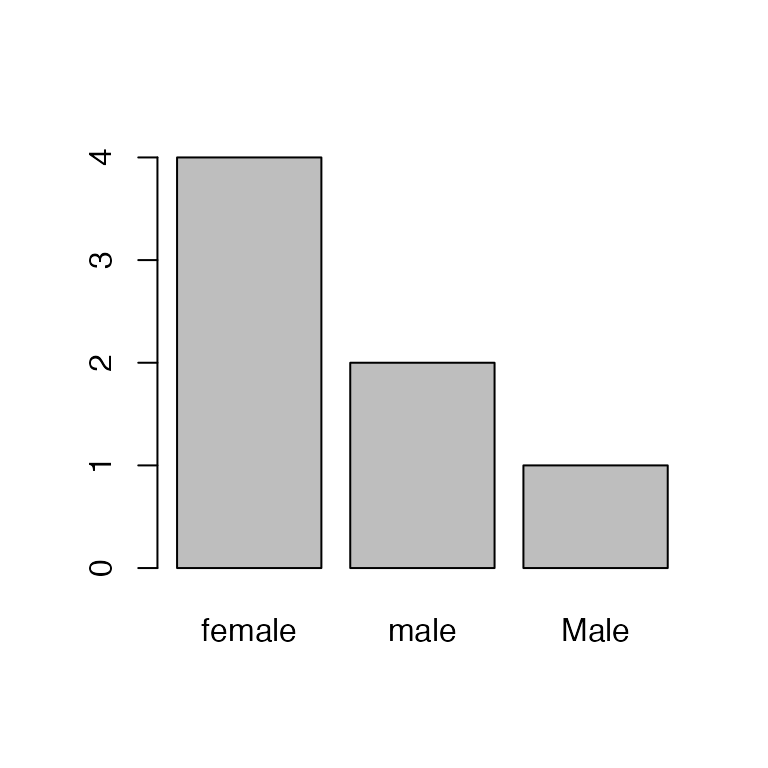

Oops, one of the field techs accidentally capitalized “Male”. Let’s change that to lowercase:

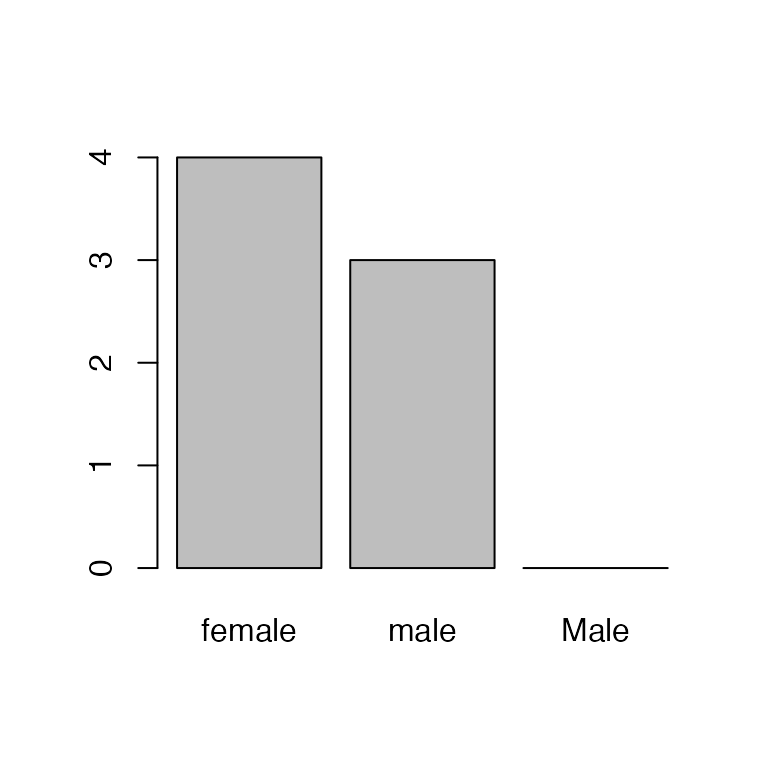

Hmm, there’s still a bar for Male. We can see what’s

happening here by looking at the levels:

levels(sex)

#> [1] "female" "male" "Male"Removing/editing the factors doesn’t change the levels! So

R still thinks there are three levels, just zero

Male entries. To remove that mis-specified level, we need

to drop it:

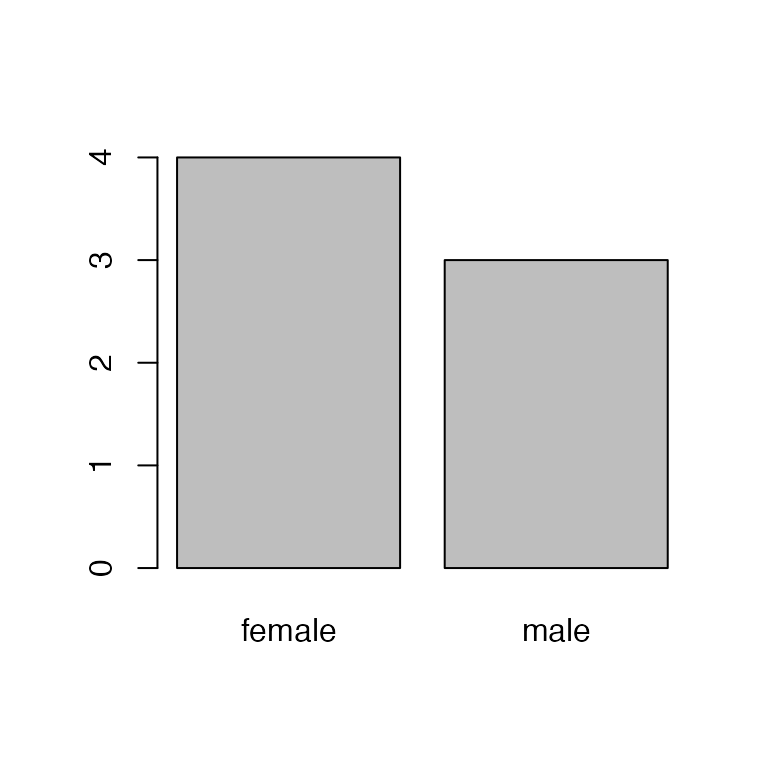

sex <- droplevels(sex)

barplot(table(sex))

That’s better.

The bottom line is be careful when working with factors, since their

behavior is not always intuitive. There are more great online resources

for working with factors in R, including this

tutorial and even a package (forcats) that tries to make it

a bit easier.

Back to the data

Before we analyze the moth data, we need to tell R to

treat the Treatment and Plot variables as

factors:

str(mothData)

#> 'data.frame': 12 obs. of 3 variables:

#> $ Treatment : chr "Control" "Control" "Control" "Control" ...

#> $ Region : int 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 ...

#> $ caterpillar: num 25 10 15 32 16 3 10 18 14 2 ...Right now, they are character and integer objects, respectively.

mothData$Treatment <- factor(mothData$Treatment, levels = c("Control", "Bt", "Dimilin"))

levels(mothData$Treatment)

#> [1] "Control" "Bt" "Dimilin"

mothData$Region <- factor(mothData$Region)

levels(mothData$Region)

#> [1] "1" "2" "3" "4"Note that we were explicit about the order of levels for

Treatment so that controls came first.

Means

Next, compute the means:

library(dplyr)

# Grand mean

(grand.mean <- mean(mothData$caterpillar))

#> [1] 14.42

# Treatment means

(treatment.means <- group_by(mothData, Treatment) %>% summarise(mu = mean(caterpillar)))

#> # A tibble: 3 × 2

#> Treatment mu

#> <fct> <dbl>

#> 1 Control 20.5

#> 2 Bt 11.8

#> 3 Dimilin 11

# Block means

(block.means <- group_by(mothData, Region) %>% summarise(mu = mean(caterpillar)))

#> # A tibble: 4 × 2

#> Region mu

#> <fct> <dbl>

#> 1 1 18.3

#> 2 2 5

#> 3 3 13.7

#> 4 4 20.7Treatment sums of squares

Remember the formula for the treatment sums of squares

\[\Large b \times \sum_{i=1}^a (\bar{y}_i - \bar{y}_.)^2\]

Block sums of squares

The formula for the block sums of squares

\[\Large a \times \sum_{j=1}^b (\bar{y}_j - \bar{y}_.)^2\]

Within groups sums of squares

\[\Large \sum_{i=1}^a \sum_{j=1}^b (y_{ij} - \bar{y}_i - \bar{y}_j + \bar{y}_.)^2\]

treatment.means.long <- rep(treatment.means$mu, each = b)

block.means.long <- rep(block.means$mu, times = a)

(SS.within <- sum((mothData$caterpillar - treatment.means.long - block.means.long + grand.mean)^2))

#> [1] 114.8NOTE: For the above code to work,

treatment.means and block.means must be in the

same order as in the original data.

Create ANOVA table

Now we’re ready to create the ANOVA table. Start with what we’ve calculated so far:

df.treat <- a - 1

df.block <- b - 1

df.within <- df.treat*df.block

ANOVAtable <- data.frame(df = c(df.treat, df.block, df.within),

SS = c(SS.treat, SS.block, SS.within))

rownames(ANOVAtable) <- c("Treatment", "Block", "Within")

ANOVAtable

#> df SS

#> Treatment 2 223.2

#> Block 3 430.9

#> Within 6 114.8Next, add the mean squares:

MSE <- ANOVAtable$SS / ANOVAtable$df

ANOVAtable$MSE <- MSE ## makes a new column!Now, the F-values (with NA for

error/within/residual row):

F.stat <- c(MSE[1]/MSE[3], MSE[2]/MSE[3], NA)

ANOVAtable$F.stat <- F.statFinally, the p-values

Quick reminder about calculating p-values

qf(0.95, 2, 6) # 95% of the distribution is below this value of F

#> [1] 5.143

1-pf(F.stat[1], 2, 6) # Proportion of the distribution beyond this F value

#> [1] 0.03922Be sure you understand what each of these functions is doing!

And we’ll display the table using kable(), with a few

options to make it look a little nicer:

options(knitr.kable.NA = "") # leave NA cells empty

knitr::kable(ANOVAtable, digits = 2, align = "c",

col.names = c("df", "SS", "MSE", "F", "p-value"),

caption = "RCBD ANOVA table calculated by hand")| df | SS | MSE | F | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 2 | 223.2 | 111.58 | 5.83 | 0.04 |

| Block | 3 | 430.9 | 143.64 | 7.51 | 0.02 |

| Within | 6 | 114.8 | 19.14 |

Blocked ANOVA using aov()

aov1 <- aov(caterpillar ~ Treatment + Region, mothData)

summary(aov1)

#> Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

#> Treatment 2 223 111.6 5.83 0.039 *

#> Region 3 431 143.6 7.51 0.019 *

#> Residuals 6 115 19.1

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1Same as what we got by hand! Look what happens if we ignore the blocking variable:

aov2 <- aov(caterpillar ~ Treatment, mothData)

summary(aov2)

#> Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

#> Treatment 2 223 111.6 1.84 0.21

#> Residuals 9 546 60.6Why is the effect of pesticide no longer significant?

Treating block effects as random effects

aov3 <- aov(caterpillar ~ Treatment + Error(Region), mothData)

summary(aov3)

#>

#> Error: Region

#> Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

#> Residuals 3 431 144

#>

#> Error: Within

#> Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

#> Treatment 2 223 111.6 5.83 0.039 *

#> Residuals 6 115 19.1

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1The values of the ANOVA table are the same as before, and there is no reason to use random effects here if interest only lies in testing the null hypothesis concerning pesticides.

Later, we will see cases where it is important to use random and fixed effects.

Assignment (not for a grade)

Some time ago, plantations of Pinus caribaea were established at four locations on Puerto Rico. As part of a spacing study, four spacings were used at each location to determine the effect of four specific spacing intervals on tree height. Twenty years after the plantations were established, measurements were made in the study plots as follows:

| Location | Spacing (ft) | Height (ft) |

|---|---|---|

| Caracoles | 5 | 72 |

| 7 | 80 | |

| 10 | 85 | |

| 14 | 91 | |

| Utuado | 5 | 75 |

| 7 | 90 | |

| 10 | 94 | |

| 14 | 112 | |

| Guzman | 5 | 88 |

| 7 | 95 | |

| 10 | 94 | |

| 14 | 91 | |

| Lares | 5 | 79 |

| 7 | 94 | |

| 10 | 104 | |

| 14 | 106 |

You can access these data using:

Questions/tasks

What is the primary null hypothesis of interest? State it, and the associated alternative hypothesis, as comments in the file

Test for effects of location and spacing on plant height using the

aov()function. NOTE: spacing must be treated as a factor, not as a numeric vectorPerform a Tukey test to determine which spacings differ

Put your answers in an R Markdown report. Your report should include:

A well-formatted ANOVA table (with caption); and

A publication-quality plot (or plots) of the estimated effect of location and spacing on plant height. The figure(s) should also have a descriptive caption and any aesthetics (color, line type, etc.) should be clearly defined.

You may format the report however you like but it should be well-organized, with relevant headers, plain text, and the elements described above.

As always:

Be sure the output type is set to:

output: html_documentBe sure to set

echo = TRUEin allRchunksSee the R Markdown reference sheet for help with creating

Rchunks, equations, tables, etc.See the “Creating publication-quality graphics” reference sheet for tips on formatting figures

Under the hood,

Ractually treats factors as integers - 1, 2, 3… - with character labels for each level↩︎